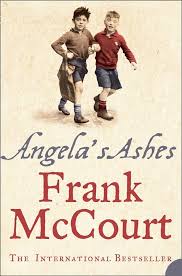

There’s a wonderful irony to calling the Savoy Hotel to speak to Frank McCourt. He couldn’t have travelled much further from the Limerick slums of his childhood, which he immortalised in his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir Angela’s Ashes.

But as his voice flows down the line, calm and wise and gnarled by the decades like a creaking oak, you sense he’s a man who would never take for granted the trappings of success.

More than 40 years of standing at the front of New York classrooms is anchoring enough for him to keep his feet firmly on the ground.

His latest book Teacher Man, the third in his memoir series, brings him to the Cheltenham Literature Festival.

“I didn’t learn much myself as a child at school in Limerick,” he says. “I learnt to be terrified. I learnt fear and trembling. There were two subjects – Irish history, all about the oppression from the British, and religious instruction.”

But one teacher did identify Frank’s talent for writing.

“There was a man called Mr O’Halloran, who looked like Franklin D Roosevelt. He called me over to him one day and said: ‘My boy, you’re a literary genius’. I’d written a piece about an astronomy book I’d read, and he liked me admitting I didn’t understand the half of it. Of course I was taunted then by all the kids in the schoolyard saying I was a literary genius. But that didn’t worry me.

“My education at that age came from reading library books. I loved reading even then. I admired the detail in Dickens’ novels in particular, and the way he wrote about something as real as poverty.

“But I was always frustrated by the inevitability of his happy endings. I could see life wasn’t really like that, so it annoyed me.”

Frank left school at 13, never imagining he would one day be a teacher himself, let alone that he would eventually be honoured as a “literary genius” by more people than Mr O’Halloran.

“I knew I’d emigrate,” he says. “My favourite dreams were the ones where I could see the New York skyline.”

Frank left behind his life as a telegram boy and made it to New York at the age of 19. “It was an intimidating place to be,” he says. “The moment you opened your mouth you were labelled as Irish, and even though I’d got there, for years I felt I was trying to find the door to properly get into America. I was in a kind of twilight zone. I had aspirations towards journalism or criminology then, but had no idea how I’d get to do these things.”

Call-up papers from the US military at the outbreak of the Korean war gave Frank an escape route from humdrum jobs in the city’s docks and warehouses.

The opportunities afforded by the services would lead to him finding his vocation in teaching.

“People said if you become a teacher you must never teach in a vocational school. There’d been a movie with Glen Ford as a teacher having a bad time with all the rough vocational students.

“Still I found myself at the McKee Vocational High School on Staten Island, and sure enough it was tough for a young teacher who didn’t really know what he was doing. But I think the kids could see that, and they gave me a break. I was interesting to them because of my Irish accent. The girls mothered me, and the boys loved the girls so didn’t upset them by giving me a hard time.

“I found it exhausting. I’d done manual jobs in the docks, but I’d never been so tired as when I got home after a day of teaching. But you learn more from the children than they learn from you, and over time you get the hang of it. You discover all the things that make your job easier.”

With the success of Angela’s Ashes in the mid 1990s, when he was in his mid-60s, Frank left teaching behind.

“I don’t regret that,” he says. “I was ready to leave. I’d been through the first act of my life, and it was time to move on to the second act. But I never imagined the success I’d have as a writer.”

It’s the sort of happy ending he’d found implausible in Dickens’ novels.

There’s a chuckle down the line as I gently point this out, and he glances around his Savoy hotel room, remembering the shared-bed slums of Limerick.

“You see,” he laughs after a moment. “That’s what you call a pregnant observation. But you’re right, I take it all back about Dickens.”

Leave a comment