November 2025 sees the release of In Danger’s Hour (preorder for Kindle now), the second part of the Romulus Hutchinson Naval Adventure Series. Following their earlier adventures in For Those In Peril, in this second instalment, we follow the twins’ service throughout 1941, from the Mediterranean to the coast of west Africa. It covers a series of key strategic operations, including Operation Demon (the British-led evacuation of Allied forces from mainland Greece in April 1941). This got me wondering – how did they come up with these obscure operational names in the first place? In this blog, I’ll examine how they came about.

The power of language

During the Second World War, the British military developed a distinctive approach to naming operations, one that reflected not only strategic intent but also a careful consideration of public perception. Winston Churchill, ever mindful of language and its power, took a personal interest in the naming of operations. He understood that a name could do more than identify a plan – it could shape morale, influence the press and, in some cases, cause distress to families of those involved. In 1943, Churchill issued a memo outlining his expectations. Operation names, he insisted, should not be boastful, frivolous or suggestive of failure. They should avoid references to living individuals and be chosen with dignity, especially given the possibility of loss of life. He warned against absurd or insensitive names, citing the hypothetical example of a mother learning her son had died in an operation called “Bunnyhug”.

Despite these guidelines, some names did push the boundaries. Operation Mincemeat, for instance, was a daring deception plan involving a corpse dressed as a British officer, planted with false documents to mislead the Germans about Allied invasion plans. The name, darkly humorous and arguably near the knuckle, reflected the macabre nature of the scheme. Yet it was never publicly known during the war and only gained notoriety decades later, by which time its success had cemented its place in history. The operation was part of a broader deception strategy under the umbrella of Operation Barclay, and its effectiveness was such that it helped divert German forces away from the real Allied target in Sicily.

Giving gravitas

Other operations followed Churchill’s advice more closely. Operation Overlord, the codename for the Normandy landings, carried a sense of authority and scale without revealing its purpose. It was suitably grand, evoking a sense of command and inevitability. Operation Dynamo, which oversaw the evacuation of Dunkirk, was named after the room in the Admiralty where the plan was conceived. Its simplicity belied the urgency and scale of the rescue effort. Operation Market Garden, the ambitious attempt to secure bridges in the Netherlands, combined the airborne assault (“Market”) with the ground offensive (“Garden”) in a way that was both descriptive and suitably neutral. While the operation itself ended in partial failure, the name avoided any suggestion of hubris or overreach.

Public reaction to operation names was generally muted during the war of course, as most were kept secret until after the fact. However, once revealed, names could take on symbolic meaning. Overlord became synonymous with liberation and Allied unity. Dynamo came to represent resilience and the spirit of survival. In contrast, Market Garden, despite its poetic name, became associated with miscalculation and the limits of ambition. The name itself was not criticised, but its association with a flawed plan led to a more reflective tone in post-war analysis.

Moral tone

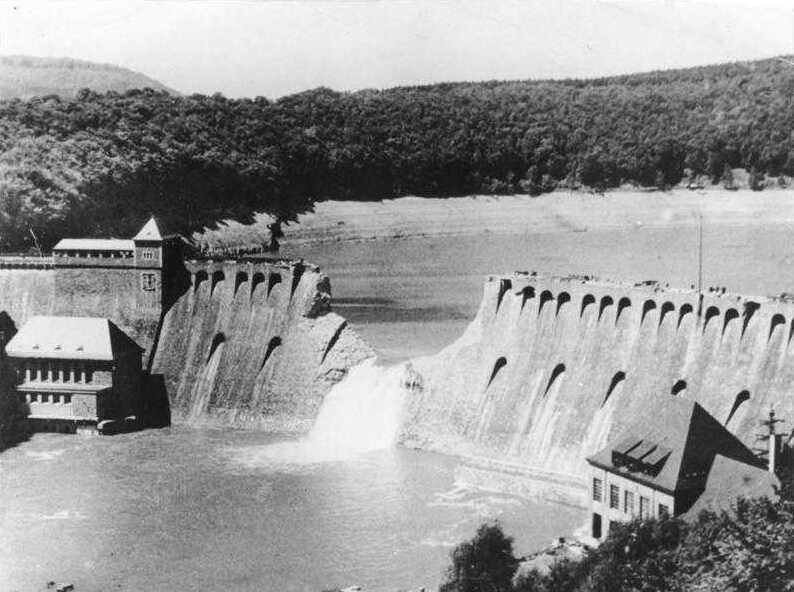

Churchill’s concern about naming was not unfounded. In the United States, some operations were given names that raised eyebrows. Operation Cornflakes, for example, involved dropping fake mailbags behind enemy lines to confuse German postal services. While clever, the name risked trivialising the effort. The British, by contrast, tended to favour names drawn from mythology, astronomy or historical figures. These offered a sense of gravitas without revealing strategic intent. Operation Chastise, the famous Dambusters raid, is a prime example. The name conveyed a sense of righteous punishment, aligning with the moral tone of the mission without giving away its target.

In the end, the British approach to naming operations during the Second World War reflected a blend of strategic caution, linguistic sensitivity and a deep awareness of public sentiment. Churchill’s insistence on dignity and restraint ensured that most operation names carried weight without courting controversy. Even when names like Mincemeat flirted with the macabre, they did so in service of a greater deception, and their legacy is one of ingenuity rather than insensitivity. The names chosen during the war continue to resonate, not just as historical footnotes, but as part of the narrative fabric of Britain’s wartime experience.

In Danger’s Hour is released in November, 2025, in paperback and Kindle formats (preorder for Kindle now), the second part of the Romulus Hutchinson Naval Adventure Series – action-packed, authentic historical fiction following twin brothers serving with the Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy during the Second World War.

Leave a comment